Wood products investigation - what we learned

/The backstory

In the fall of 2014 we helped our partner community Arimae thin out its own reforestation project. The stand had not been properly thinned since it was established about 17 years ago, and the overcrowding was preventing development of the more viable trees.

While we wanted to help the community improve its own forestry projects—which will in turn yield more profit for the community down the road—we also wanted the experience of managing a thinning, called raleo in Spanish. With our earliest investor-owned forests approaching eight years, they would soon need their own raleo, and working with the community's project was a low-risk way to cut our teeth. We held numerous meetings with the community, and completed a profit sharing agreement that would compensate them once we sold the wood to a buyer.

The raleo

Over the course of a few months beginning in late 2014, our field team of laborers and our foreman felled the smaller trees, aggregated them into pickup points and hauled them to the road using horses, tractors, and their own manpower. From there they loaded them into trucks and carted them a couple miles down the road to a storage facility.

Workers Load a Spanish Cedar Log into the truck.

We expected to quickly find a buyer for the roughly 10,000 board feet of mahogany, spanish cedar and spanish oak on our hands. But with the market saturated with cheap, illegally harvested timber from the Darien, we found low demand for our smaller-diameter timber. Initially, we worked with a small indigenous organization who was exporting logs on behalf of the nearby indigenous reservations. Soon after we started working with them, they closed and we then worked with local connections and posted ads in local publications to gin up leads. At the same time, we pursued leads with our own international contacts to export the timber after necessary processing in Panama. All of these efforts failed to generate an economically viable and real sale of the timber.

Taking matters into our own hands

Sitting on the wood for 9 months was frustrating because we were paying to store the wood, and the community wanted their share of the profit that we anticipated turning on the wood. With no guarantee that we would be able to sell the wood anytime soon, we bought out the community's stake, making us the full owners of the logs.

Logs delivered to the holding location

To get the most value from the raw logs we now owned, we would have to invest in processing the logs into lumber, and then process them further into finished products. Then, we'd have to get those products to market. In other words, we'd need to participate in each step in the value chain: milling, drying, processing, transporting, designing, manufacturing, exporting and marketing finished products.

Could we evolve from a forestry project developer into a company selling consumer products with a sexy story?

Researching options for production in Panama

In October 2015 I, along with our field supervisor Francisco and field coordinator Yem, visited numerous woodshops in the Darién to pose the idea of making wooden products for us on contract. Of the roughly ten we visited, we deemed that a couple of them had the right equipment, organization and level of interest to work. We promised to come back to them with more detailed design parameters and instructions. Knowing that there was an opportunity to work with local labor, and for a reasonable price, was a good first step.

What are the most popular products?

But we also wanted to know what the potential demand for the products might be. In November 2015 we published a voting page on our website, displaying wooden products representative of those we could potentially make with the logs. We attempted to post products that were diverse, but also that could be realistically made given the limitations of the log dimensions and the current work being produced by the woodshops in Panama. We asked people to vote on their favorites to gauge which would be the most likely to sell if we were to make them. After several weeks of voting, we knew the favorites: cheese boards, candle holders and coasters.

While understanding the demand for these existing products was useful, we would also be competing with all the other cheese boards, candle holders and coasters out there.

New ideas with product designers

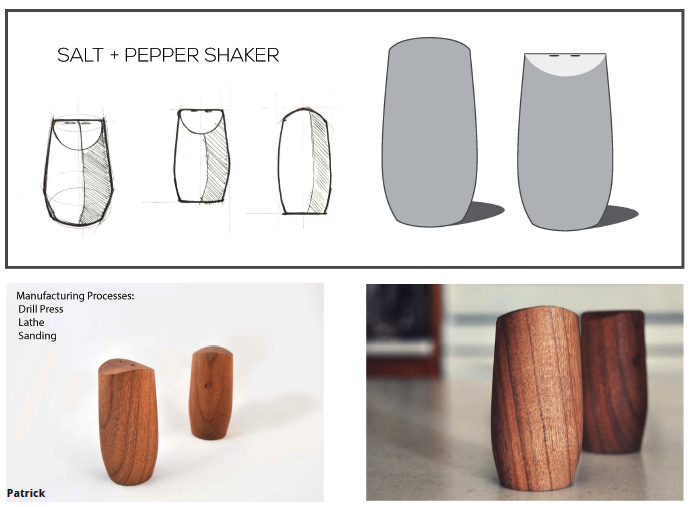

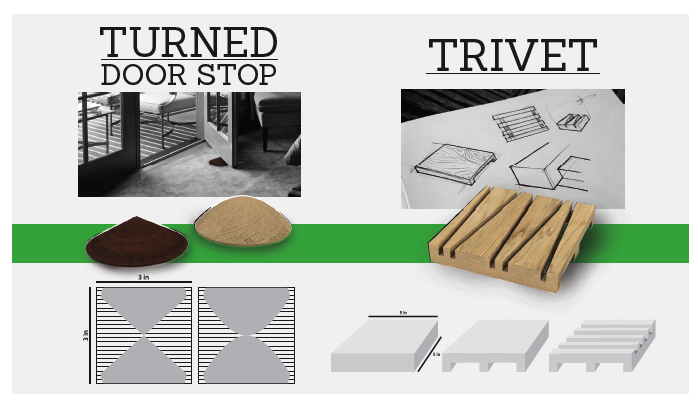

To explore new product concepts, I conducted a five-week project with seven product design students (juniors and seniors) and my former design professor at Virginia Tech. The goal was to generate new product ideas based on the characteristics of the wood in Panama, and the Panamanian woodworkers’ existing equipment and working style. Students began with loose concept sketches, refined them based on feedback, and eventually produced prototypes of their products. Here are some of their ideas.

The sale happened after all

And this is as far as we got. As we continued testing the waters for finished products strategy, we finally found someone interested in buying the raw wood. We debated about keeping the wood and continuing to push on the products strategy, but ultimately decided that selling the wood and cutting our losses made more sense than investing in the daunting process of launching a wooden products line.

We appreciate everyone who participated in our products survey on our website, the Virginia Tech design students who worked with me on new product concepts, and the woodworkers in Panama for their willingness to hear our ideas.